Impedance Measurements

|

In this section, we'll be concerned with measuring the impedance of an antenna. As stated previously, the impedance is a fundamental parameter for antennas. If the impedance of an antenna is not "close" to that of the transmission line (most often 50 Ohms), then very little power will be transmitted by the antenna (if the antenna is used in the transmit mode), or very little power will be received by the antenna (if used in the receive mode). Hence, without proper impedance (or an impedance matching network), our antenna will not work properly.

Before we begin, I'd like to point out that objects placed around the antenna can alter its radiation pattern as well as its impedance. For example, an antenna could be designed to sit on top of a metal surface (as in an airplane antenna), or it may be designed to be integrated within many other metallic components (as in a mobile phone antenna). Consequently, for the best accuracy the impedance should be measured in an environment that will most closely resemble where it is intended to operate. The term driving point impedance is sometimes used to mean the input impedance measured in a particular environment, and self-impedance or stand-alone impedance is the impedance of an antenna in free space, with no objects around to alter its radiation pattern.

Fortunately, impedance measurements are pretty easy if you have the right equipment. In this case, the right equipment is a Vector Network Analyzer (VNA). This is a measuring tool that can be used to measure the input impedance as a function of frequency. Alternatively, it can plot S11 (return loss), and the VSWR, both of which are frequency-dependent functions of the antenna impedance. The Agilent 8510 Vector Network Analyzer is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The popular Agilent (HP) 8510 VNA.

There are also lower cost VNAs that don't have a display integrated, such as the VNA from Copper Mountain Tech. In Figure 1b, N-type to SMA coaxial cables are used to connect the VNA to the test antennas. A Horn Antenna and a Wideband Dipole Antenna are measured.  Figure 1b. 2-Port VNA. This model functions from 300kHz to 8.5GHz.

A R&S VNA is also shown measuring a loop antenna in Figure 1c. Note that the antenna is measured on a styrofoam block. Styrofoam has virtually no impact to antenna impedance (at RF frequencies, the material basically looks like air).

Figure 1c. Rohde and Schwarz VNA Measuring a Loop Antenna.

Moving on, suppose we want to perform an impedance measurement from 400-500 MHz. Step 1 is to make sure that our VNA is specified to work over this frequency range. Network Analyzers work over specified frequency ranges, which go into the kHz range (30 kHz or so) and up into the high GigaHertz range (110 GHz or so, and these tend to cost in the hundreds of thousands of US dollars). Once we know our network analyzer is suitable, we can move on.

Next, we need to calibrate the VNA. This is much simpler than it sounds. We will take the coaxial cables that we are using for probes (that connect the VNA to the antenna) and follow a simple procedure so that the effect of the cables (which act as transmission lines) can be calibrated out. To do this, typically your VNA will be supplied with a "cal kit" which contains a matched load (50 Ohms), an open circuit load and a short circuit load. We look on our VNA and scroll through the menus till we find a calibration button, and then do what it says. It will ask you to apply the supplied loads to the end of your cables, and it will record data so that it knows what to expect with your cables. You will apply the 3 loads as it tells you, and then your done. Its pretty simple, you don't even need to know what you're doing, just follow the VNA's instructions, and it will handle all the calculations. There's also automatic e-cal kits, which use switches to perform the open/short/thru measurements for you.

Now, connect the VNA to the antenna under test. Set the frequency range you are interested in on the VNA. If you don't know how, just mess around with it till you figure it out, there are only so many buttons and you can't really screw anything up.

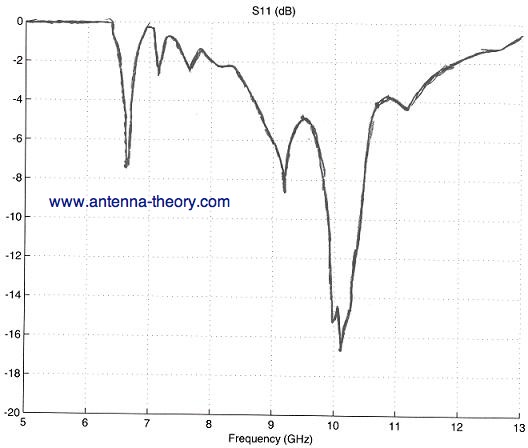

If you request output as an S-parameter (S11), then you are measuring the return loss. In this case, the VNA transmits a small amount of power to your antenna and measures how much power is reflected back to the VNA. A sample result (from the slotted waveguides page) might look something like:

Figure 2. Example S11 measurement.

Note that the S-parameter is basically the magnitude of the reflection coefficient, which depends on the antenna impedance as well as the impedance of the VNA, which is typically 50 Ohms. So this measurement typically measures how close to 50 Ohms the antenna impedance is.

Another popular output is for the impedance to be measured on a Smith Chart. A Smith Chart is basically a graphical way of viewing input impedance (or reflection coefficient) that is easy to read and displays magnitude and phase information simultaneously. The center of the Smith Chart represented zero reflection coefficient, so that the antenna is perfectly matched to the VNA. The perimeter of the Smith Chart represents a reflection coefficient with a magnitude of 1 (all power reflected), indicating that the antenna is very poorly matched to the VNA. The magnitude of the reflection coefficient (which should be small for an antenna to receive or transmit properly) depends on how far from the center of the Smith Chart you are. As an example, consider Figure 3. The reflection coefficient is measured across a frequency range and plotted on a Smith Chart.

Figure 3. Smith Chart Graph of Impedance Measurement versus Frequency.

In Figure 3, the black circular graph is the Smith Chart. The black dot at the center of the Smith Chart is the point at which there would be zero reflection coefficient, so that the antenna's impedance is perfectly matched to the generator or receiver. The red curved line is the measurement. This is the impedance of the antenna, as the frequency is scanned from 2.7 GHz to 4.5 GHz. Each point on the line represents the impedance at a particular frequency. Points above the equator of the Smith Chart represent impedances that are inductive - they have a positive reactance (imaginary part). Points below the equator of the Smith Chart represent impedances that are capacitive - they have a negative reactance (for instance, the impedance would be something like Z = R - jX).

To further explain Figure 3, the blue dot below the equator in Figure 3 represents the impedance at f=4.5 GHz. The distance from the origin is the reflection coefficient, which can be estimated to have a magnitude of about 0.25 since the dot is 25% of the way from the origin to the outer perimeter.

As the frequency is decreased, the impedance changes. At f = 3.9 GHz, we have the second blue dot on the impedance measurement. At this point, the antenna is resonant, which means the impedance is entirely real. The frequency is scanned down until f=2.7 GHz, producing the locus of points (the red curve) that represents the antenna impedance over the frequency range. At f = 2.7 GHz, the impedance is inductive, and the reflection coefficient is about 0.65, since it is closer to the perimeter of the Smith Chart than to the center.

In summary, the Smith Chart is a useful tool for viewing impedance over a frequency range in a concise, clear form.

Finally, the magnitude of the impedance mismatch is often measured via VSWR (Voltage Standing Wave Ratio). The VSWR is a function of the magnitude of the reflection coefficient, so no phase information is obtained about the impedance. However, VSWR gives a quick way of estimated how much power is reflected by an antenna. Consequently, in antenna data sheets, VSWR is often specified, as in "VSWR: < 3:1 from 100-200 MHz". Using the formula for the VSWR, you can figure out that this means that less than half the power is reflected from the antenna over the specified frequency range. Note that S11, Smith Chart, and VSWR measurements are all the same type of measurement, just formatted differently depending on the user's preference.

Isolation MeasurementsThe above VNA measurements are done with a single port. Often VNAs are capable of measuring 2-ports (sometimes 4-port, and there are some that go as high as 24ports!). If you connect an antennas to each port (for example, as shown in Figure 1b above), then S11 is the impedance of the antenna on port1, and S22 is the impedance of the antenna on port 2. The VNA also measures the coupled power between the antennas, which is S12 or S21 (for antennas, these values will be identical due to reciprocity). S12/S21 is commonly referred to as isolation. Isolation is a measure of how strongly the antennas couple together. For example, if you have two WIFI antennas in your product, you want them to have a high isolation (it's debatable on the exact value required, but below -15 dB is a good number). High isolation means the antennas operate independently. Low isolation (such as S12 larger than -8 dB) means the antenans couple together strongly, which degrade their antenna efficiency. Low isolation also means the antennas correlate very strongly, which ultimately defeats the purpose of having multiple antennas. An example of an S12 measurement is shown in Figure 4. This is for 2-WIFI antennas in the same product. The frequency bands of interest are 2.4-2.484 GHz [wifi 802.11b/g] and 5.15-5.85GHz [802.11a/ac]. The isolation is under -15 dB, which is good. Unlike S11/impedance measurements, S12 is almost always plotted in dB as shown.

Figure 4. S12 [Isolation or Coupling] is Plotted for 2-WIFI Antennas in dB.

In summary, impedance is measured with a VNA, and can be displayed in various ways include the Smith Chart, VSWR and S11. We care about the impedance of an antenna so that we can properly transfer/receive power to/from the antenna from/to the transmitter/receiver. VNAs enable us to measure an antenna's impedance (the V in VNA means vector, so that we can measure magnitude and phase) as well as the isolation between different antennas. In the next Section, we'll look at scale model measurements.

|

Antenna Measurements (Home)

Copyright antenna-theory.com, 2010-2021. Feel free to reference this site with proper citation.